II. The logic of violence

|

|

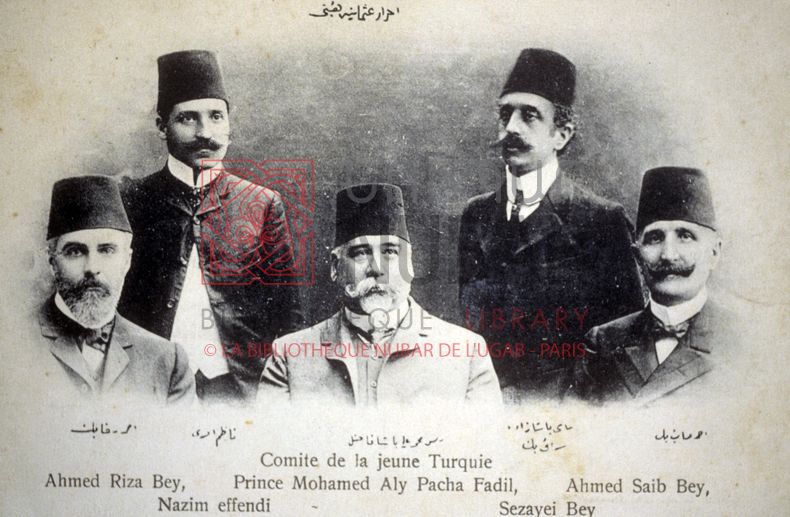

1. THE INCREASE IN POWER OF THE COMMITTEE OF UNION AND PROGRESS

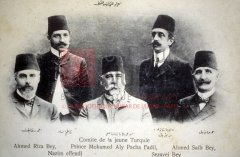

Ideology and Influence of the Young Turks

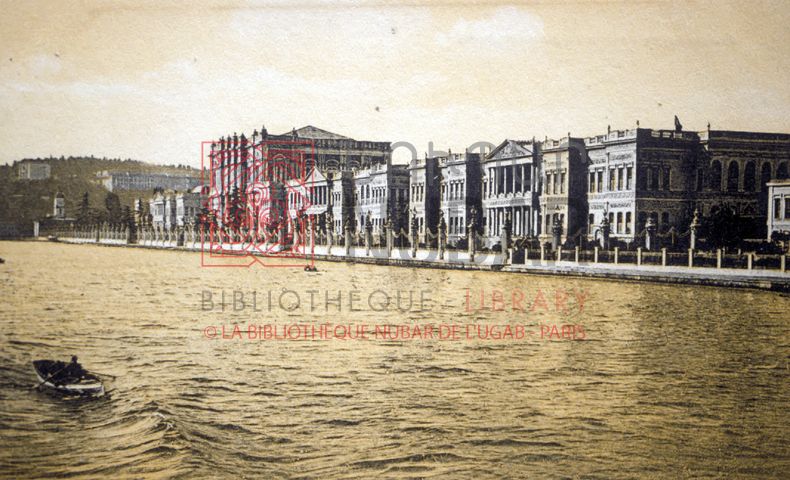

Mehmed Talât, Ismail Enver and Halil Bey, prominent members of the CUP (photo published in Alfred Nossig, Die Neue Türkei und ihre Führer, Halle : O. Hendel, undated [1916], p. 8).Dolmabahçe Palace, headquarters of the Committee of Union and Progress. (Michel Paboujian Collection).

From 1908 to 1918, the Ottoman Empire was led, almost without interruption, by the Committee of Union and Progress, a party fully controlled by a central committee of nine members constituting a hidden power.

Despite the hopes they had been stirred in its rise to power, by dangling the establishment of true equality within the Ottoman Empire between Muslims, Christians and Jews, leaders of the CUP were largely imbued with a European-inspired social Darwinist ideology. In their eyes, the mission of the CUP was to regenerate the “Turkish race.”

Mainly composed of officers and members from the geographical margins of the empire, essentially from the Balkans and the Caucasus, the CUP cemented its power by developing a network of local clubs, and gradually replacing the army officers and the heads of the administration with party activists or sympathizers. Meanwhile, the CUP has forged close ties in the provinces with local elders as well as religious and tribal leaders. All these ramifications favored his influence on the ground, and later proved to be great supporters at the time of the implementation of the genocide.

|

|

The Balkan Wars and Internal Crisis

Between the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the coup on January 25, 1913, which established a one-party regime, leaving the Committee of Union and Progress to do what it pleased, internal and external crises multiplied and contributed to the radicalization of its leaders.

Following the Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913 and the humiliating defeat of Ottoman forces by allied Balkan nations that led to the loss of almost all the remaining Ottoman territories in Europe, the most radical elements within the CUP took power.

|

|

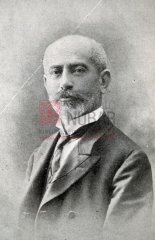

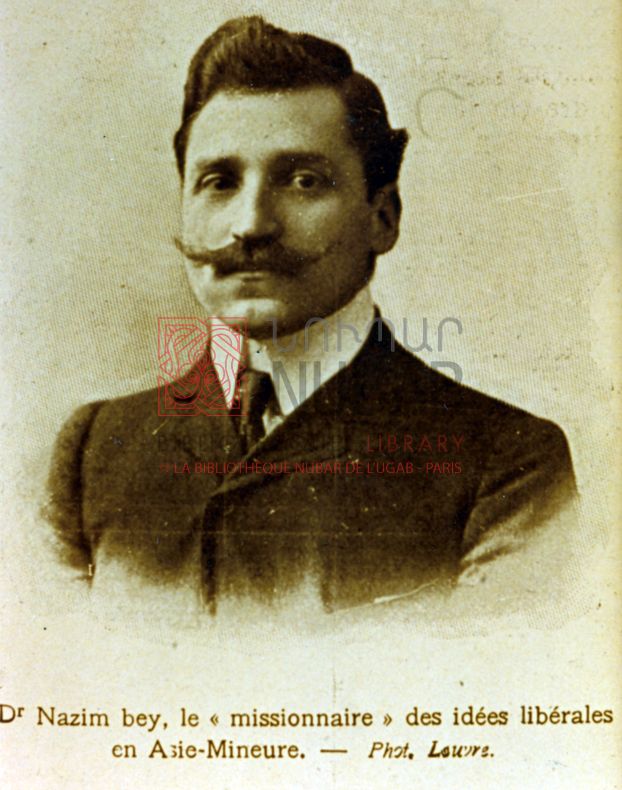

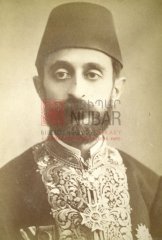

Doctor Mehmed Nâzım (1870-1926), member of the Unionist Central Committee.

He was one of the heads of the Special Organization (Teskilât-ı Mahsusa) during the genocide (Mekhitarists Fathers Collection, Venice).

|

Mehmed Talât (1874-1921), head of the Unionist Central Committee, Minister of the Interior. Strongman of the regime and the Party, he influenced the most radical elements inside the CUP. (AGBU Nubar Library, Paris).

|

Ismail Enver (1881-1922), member of the Unionist Central Committee, Minister of War.(AGBU Nubar Library, Paris). |

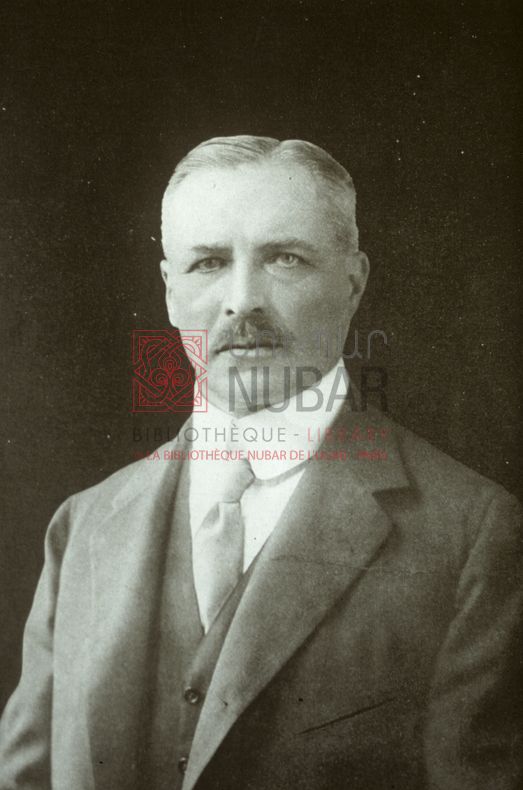

Ahmed Cemal [Jemal] (1872-1922) member of the Unionist Central Committee, Minister of the Navy commander-in-chief of the Forth Ottoman Army on the Syrian, Mesopotamian and Palestinian fronts. (AGBU Nubar Library, Paris). |

|

2. THE REFORM PROJECT IN ARMENIA: A LAST CHANCE AT COEXISTENCE

Dispossession and Lasting Insecurity

The Etchmiadzin Cathedral in the early 20th century. (AGBU Nubar Library, Paris).

The ascent of the Young Turks was perceived as progress and an opportunity to implement reforms that would improve the safety of the Armenian population in the Eastern provinces. After four years of fruitless efforts, while the Eastern provinces were rid of their population because of mass emigration caused by insecurity and misery, the Armenian authorities decided in October 1912 to internationalize the issue of reform. The Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin, the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, Armenian political parties and some individuals then participated in negotiations between the Sublime Porte and the Great Powers.

|

hommes politiques arméniens

Gabriel Noradounghian (1852-1936), haut-fonctionnaire, ministre des Affaires étrangères de l’Empire ottoman de juillet 1912 à janvier 1913 (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-1_result.jpg

Krikor Zohrab (1861-1915), photographié en 1913. Député au parlement ottoman, avocat, écrivain, il fut la cheville ouvrière des négociations menées avec les ambassades des grandes puissances en faveur des réformes en Arménie (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II. 2-2_result.jpg

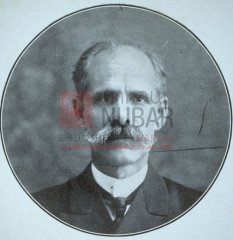

Boghos Nubar Pacha (1851-1930), fils de l’ancien premier ministre d’Égypte Nubar Pacha, président de la Délégation nationale arménienne (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-3_result.jpg

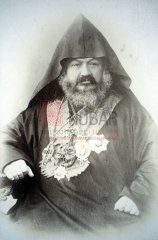

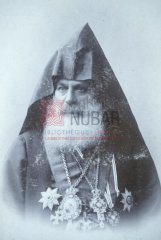

Kévork V Tiflisétsi (1847-1930), catholicos d’Etchmiadzine, l’un des initiateurs du projet de réforme dans les provinces arméniennes ottomanes (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-4_result.jpg

Zaven Yéghiayan (1868-1947), patriarche des Arméniens de Constantinople de 1913 à 1922 (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-5_result.jpg

Hampartsoum Boyadjian (1867-1915), député du parti hentchag au Parlement ottoman et à la Chambre arménienne (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-6_result.jpg

Vartkès (Hovhannès Séringiulian), 1871-1915, député tachnag au Parlement ottoman et à la Chambre arménienne (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-9_result.jpg

Simon Zavarian, 1865-1913, agronome, membre fondateur de la fédération révolutionnaire arménienne ou parti tachnag (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.2-7_result.jpg

|

The Plan for Reform

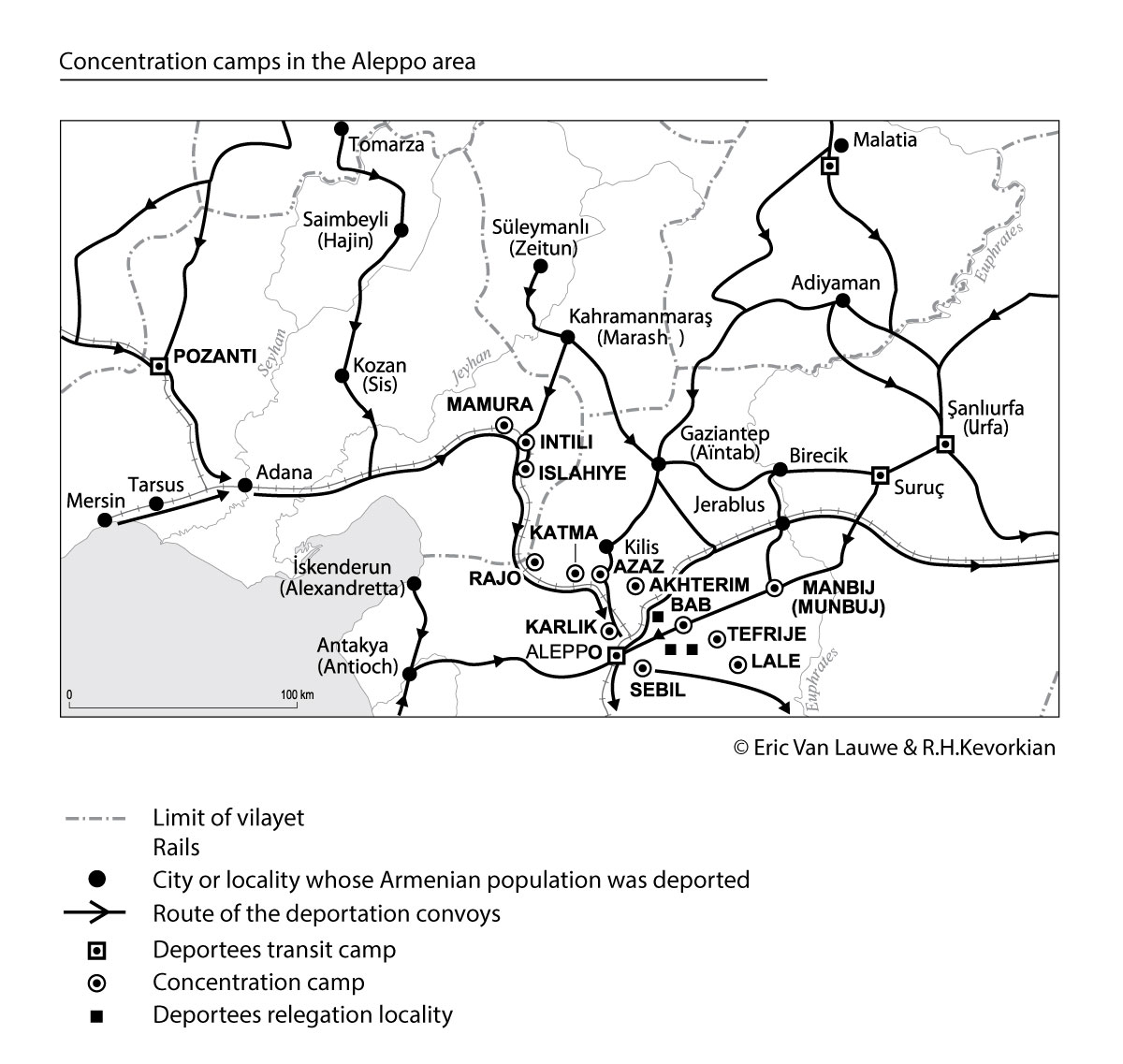

Baron Hans Von Wangenheim, German ambassador to Constantinople, negociator in the plan for reform in Armenia (The World’s Work, vol. 36, 1918).On December 25, 1913, the Germans and Russians officially submitted a draft reform to the Ottoman government. The plan called for the unification of the six Eastern “Armenian” vilayets; the appointment of a Christian governor, either Ottoman or European; the appointment of a board of directors and a joint provincial assembly, both Muslim and Christian; the formation of a joint police force; the dissolution of the hamidiye brigades created during the reign of Abdülhamid II, which were still active; the formation of a commission to examine the confiscation of land that had occurred in preceeding decades, etc. On February 21, 1914, the Sublime Porte ultimately accepted the agreement, without being able to remove the clause about foreign control which would be established to monitor the effective implementation of reforms in the Armenian provinces. Two general inspectors from Norway and the Netherlands were nominated but did not have the chance or the time to actually fulfil their roles, because of the outbreak of war.

|

|

3. THE WORLD WAR AND THE RADICALIZATION OF UNIONIST LEADERS AGAINST THE ARMENIANS

(JANUARY 1914 TO MARCH 1915)

|

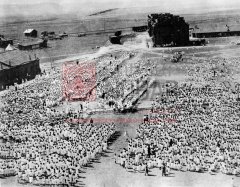

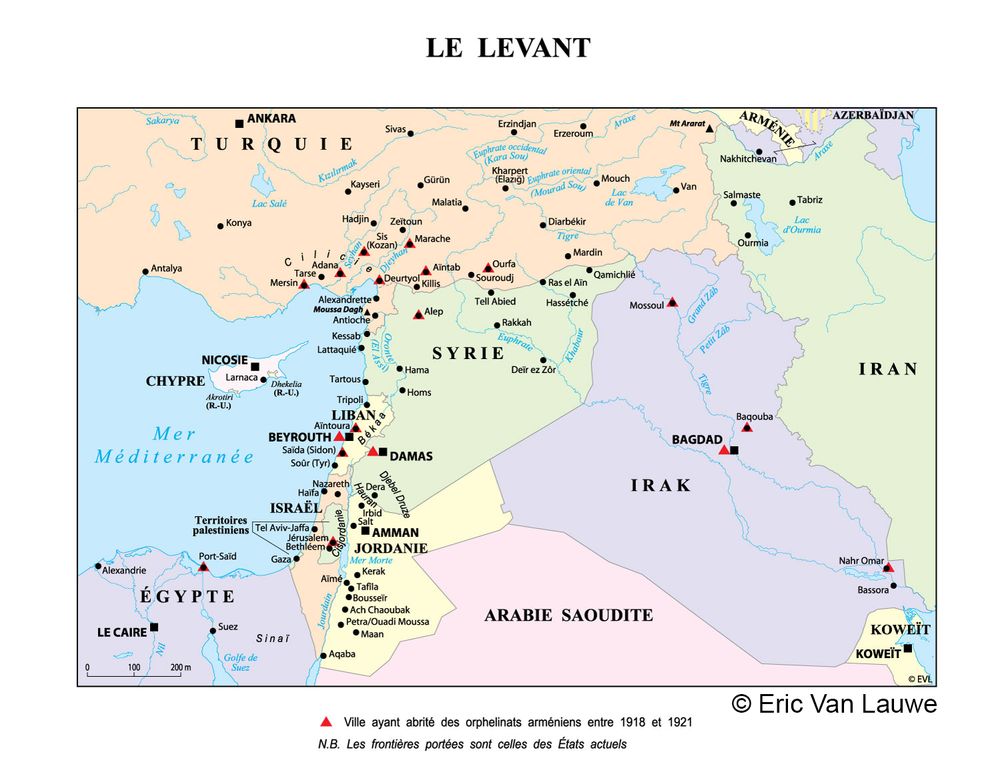

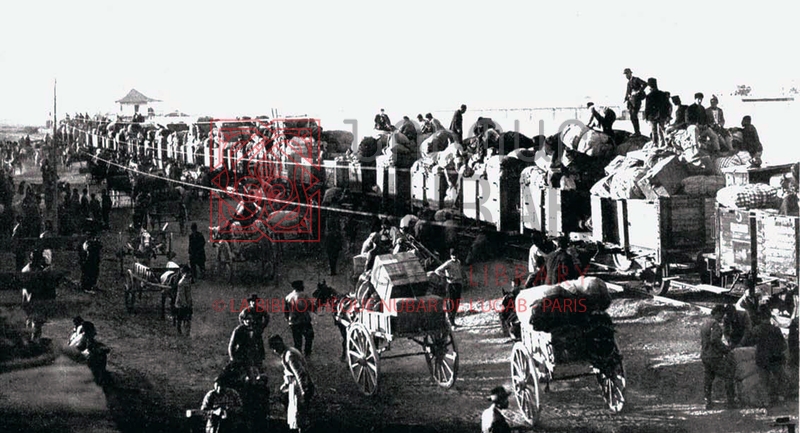

Ottoman troops mobilized at the railway station in Istanbul, August 1914. (photo by Victor Forbin, British Foreign office archives, Kew).

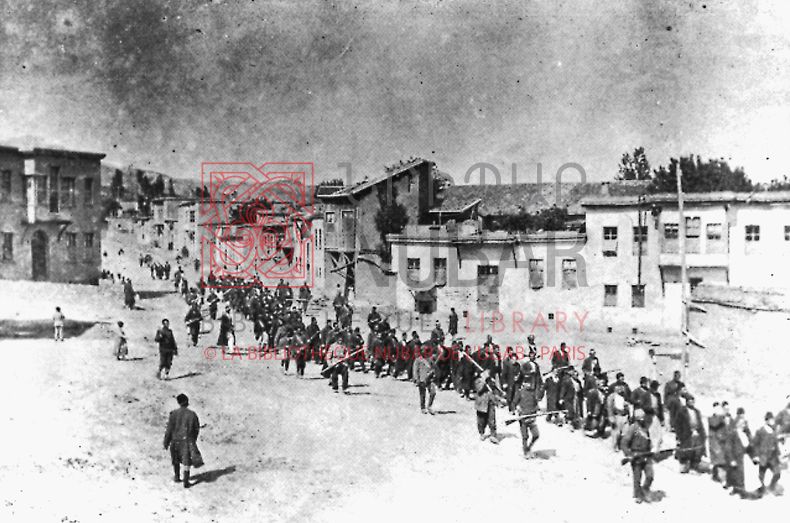

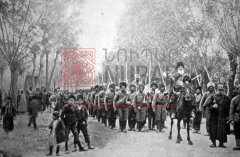

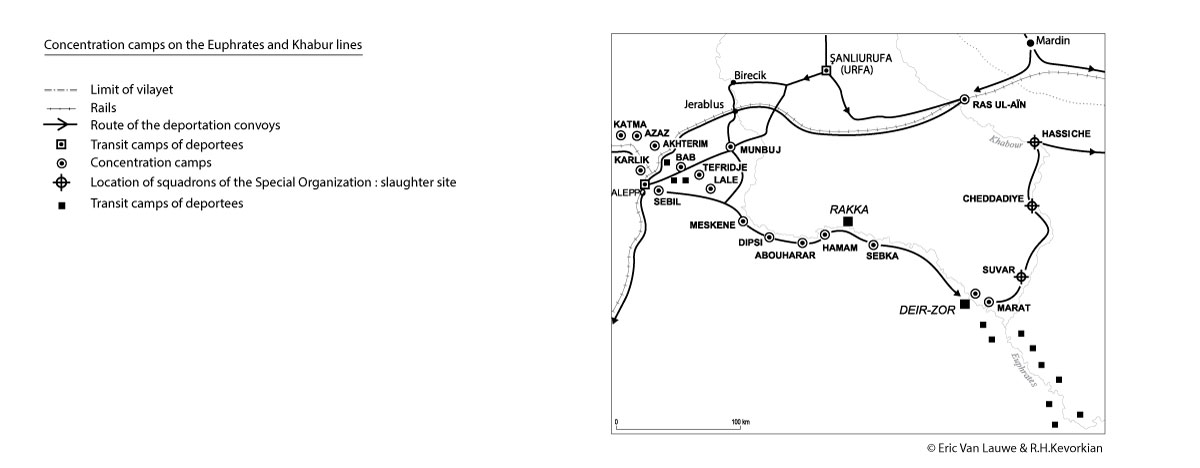

The Ottoman Empire entered the war alongside the Central Powers in October 1914, but the general mobilization had already been decreed in the month of August. Armenian men aged 20 to 40, i.e. the “lifeblood” of the Armenian millet, had been mobilized and thus neutralized. It is in this favorable context, while the great powers were themselves facing full-scale war, that the Unionist leaders accelerated their policy of ethnic homogenization of Asia Minor by making the decision to destroy the Armenian and Syriac communities of the Empire.

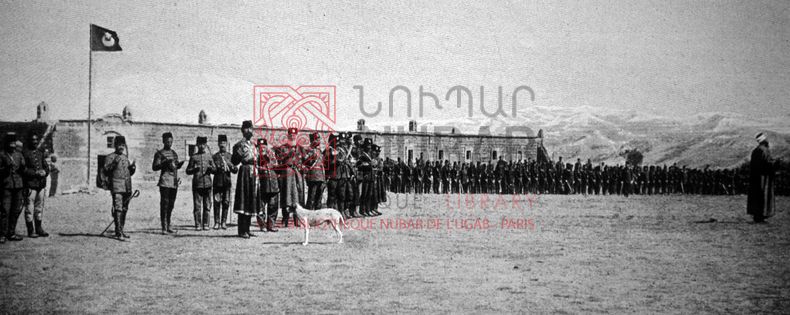

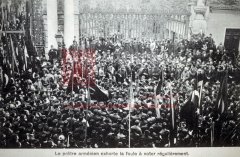

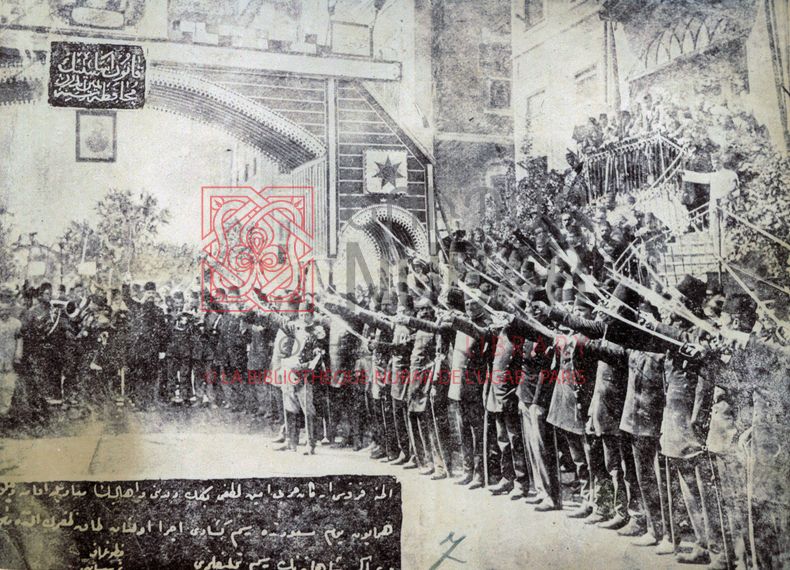

General mobilization and parade of Ottoman troops, Constantinople, November 1914 (AGBU Nubar Library, Paris).

At the end of December 1914, after the scathing defeat suffered by the Ottoman army in Sarıkamış on the Russian front, the Central Committee of the CUP adopted a radical policy against the Ottoman Armenians. The Central Committee of the CUP was formed by Mehmed Talât, Midhat Şükrü, Dr. Nazım, Kara Kemal, Yusuf Rıza, Ziya Gökalp, Eyub Sabri [Akgöl], Dr. Rüsûhi, Dr. Bahaeddin Şakir and Halil [Menteşe].

|

entree en guerre

Mobilisation générale, parade des troupes ottomanes, automne 1914 (coll. Pères mekhitaristes de Venise).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/2_result.jpg

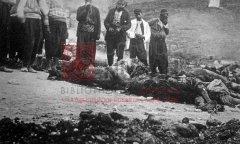

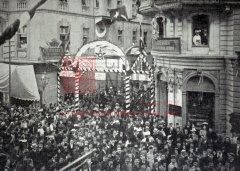

Constantinople, 14 novembre 1914 : déclaration du djihad par le cheikh ul-Islam [şeyhülislam], en présence des dirigeants jeunes-turcs (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar)

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/4_result.jpg

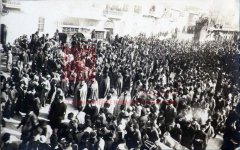

Manifestation des corporations à Constantinople, le 14 novembre 1914, à l’occasion de l’appel à la guerre sainte (coll. Pères mekhitaristes de Venise).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/5_result.jpg

Erzerum, août 1914 : huitième congrès du parti tachnag, où le CUP tenta en vain d'obtenir l'appui de la FRA contre les Russes (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/7_result.jpg

Manifestation patriotique à l’occasion de l’appel à la guerre sainte (photographie de Victor Forbin, archives du Foreign Office, Kew).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/6_result.jpg

Officiers turcs et allemands sur le front de Palestine. Quelque 18 000 militaires allemands, en majorité des officiers, appuyaient et conseillaient les forces ottomanes sur le front d’Orient (coll. Pères mekhitaristes de Venise).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/8_result.jpg

Le ministre de la Guerre, Enver pacha, sur le chantier du Bagdadbahn à Bozanti en compagnie d’officiers allemands (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/9_result.jpg

Constantinople, 1916 : réception de l’empereur d’Allemagne Guillaume II. De gauche à droite : Enver, le cheikh ul-Islam, Abbas Hilmi Pacha, Talât et le sultan Mehmed V (coll. Michel Paboudjian).

http://localhost:8888/bnulibrary/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/10_result.jpg

|

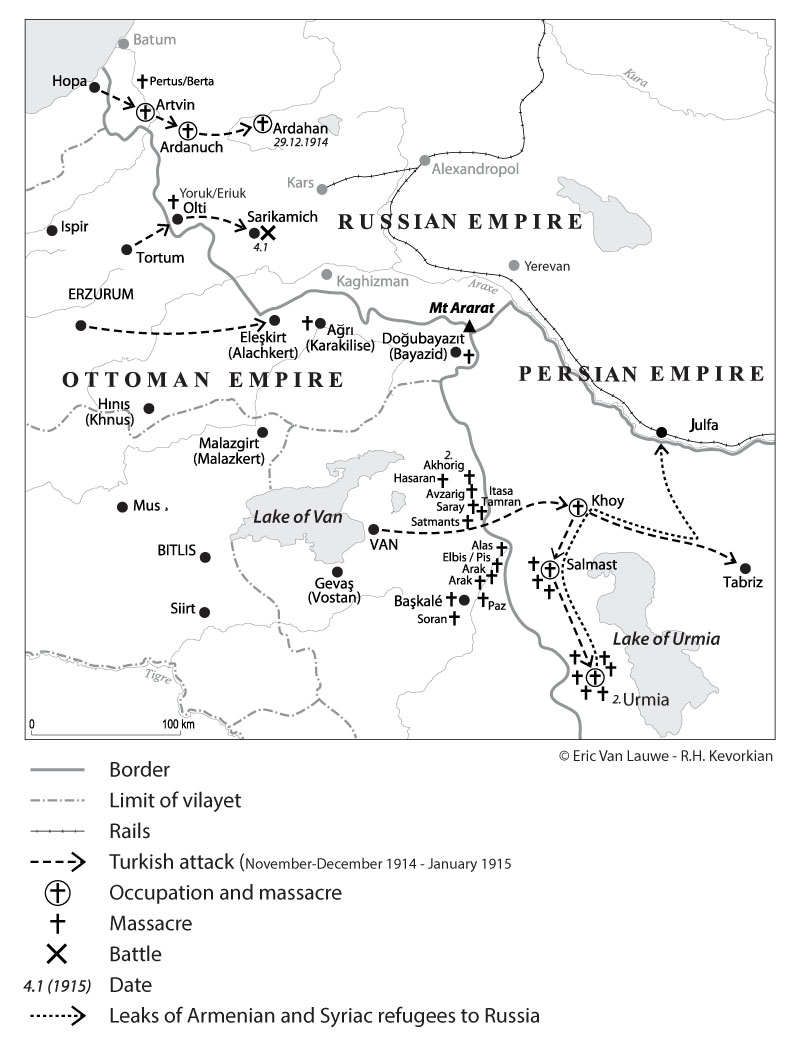

EARLY MASS VIOLENCE ON THE CAUCASIAN FRONT (DECEMBER 1914 TO FEBRUARY 1915)

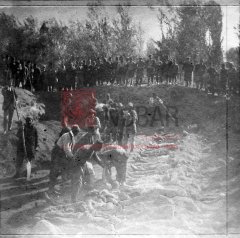

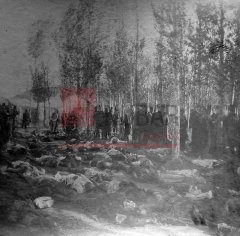

The Ottoman offensive on the Caucasian front was accompanied by localized massacres, particularly in the region of Artvin and along the border with Persia, where the Armenian population of twenty villages was massacred, just as in Persian Azerbaijan, where Ottoman troops, backed by Kurdish tribal leaders, annihilated Armenian villagers living of the plains of Khoy, Salmast and Urmia.

|

English (UK)

English (UK)  Français (FR)

Français (FR)

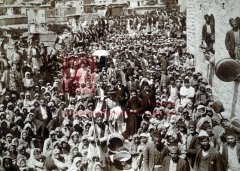

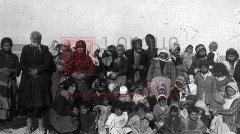

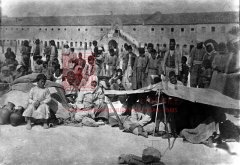

![Arméniens de Zeytoun déportés et momentanément emprisonnés à Marache [Kahramanmaraş] (coll. Musée Institut du génocide, Erevan). Arméniens de Zeytoun déportés et momentanément emprisonnés à Marache [Kahramanmaraş] (coll. Musée Institut du génocide, Erevan).](http://bnulibrary.org/images/jsn_is_thumbs/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section03/Zeytountsi_Marache.jpg)

![Ahmed Cemal [Djemal] (1872-1922), membre du comité central unioniste, ministre de la Marine Ahmed Cemal [Djemal] (1872-1922), membre du comité central unioniste, ministre de la Marine](/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/II.1-11_result.jpg)

![Constantinople, 14 novembre 1914 : déclaration du djihad par le cheikh ul-Islam [şeyhülislam], en présence des dirigeants jeunes-turcs (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar) Constantinople, 14 novembre 1914 : déclaration du djihad par le cheikh ul-Islam [şeyhülislam], en présence des dirigeants jeunes-turcs (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar)](http://bnulibrary.org/images/jsn_is_thumbs/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section02/4_result.jpg)

![Fiche d’identité de Tavit Hayriguian, pensionnaire à l’orphelinat Araradian de Jérusalem depuis le 10 février 1922, âgé de 9 ans, fils de Daniel et Mariam, originaires de Siirt [Seghert], déportés à Mossoul et décédés (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar). Fiche d’identité de Tavit Hayriguian, pensionnaire à l’orphelinat Araradian de Jérusalem depuis le 10 février 1922, âgé de 9 ans, fils de Daniel et Mariam, originaires de Siirt [Seghert], déportés à Mossoul et décédés (coll. Bibliothèque Nubar).](http://bnulibrary.org/images/jsn_is_thumbs/images/expos_virtuelles/armenie1915/section04/rehabiliter/09_8_jerusalem_bnu.jpg)