| VIRTUAL EXHIBITION - ARMENIA 1915 |

|

Memoirs of Halil Menteşe, Ottoman Minister of Foreign Affairs. |

| INTRODUCTION

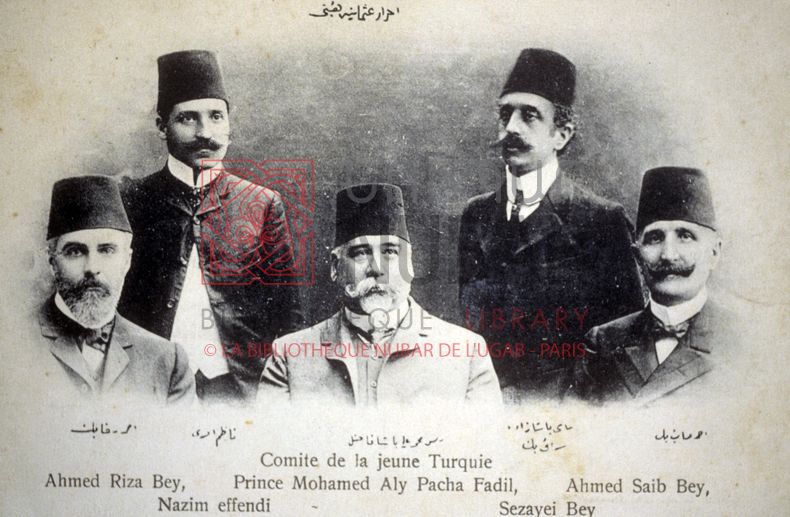

The rise to power of the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terraki), or the CUP, in July 1908 generated immense hope among people persecuted under the former autocratic regime of the Sultan. But it also promoted the quest for a new political model: an ethnically homogeneous nation-state. For Unionist leaders, this was the only option for regenerating a weakened Ottoman Empire. However, such a project implied the exclusion of groups considered impossible to assimilate or whose existence was perceived as an obstacle to the unification of the empire and its inhabitants. After successive territorial losses in the late 19th century, the humiliating defeat in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) shifted the balance within the Unionist Central Committee in favor of its most radical members. Boycott campaigns encouraged by the authorities against Greek and Armenian-owned businesses contributed to instilling among the Muslim population the image of the Greek and Armenian “traitor.” This process of stigmatization—feeding off the legacy of the old Ottoman regime, including massacres that had already afflicted the Armenians between 1894 and 1896—had undoubtedly prepared minds for genocide to be seen as a legitimate “punishment” inflicted on the Greeks, Syriacs and Armenians. |

English (UK)

English (UK)  Français (FR)

Français (FR)